№ 63: They Accused Me of Collusion, Confiscated My $$$ and Taught Me A Priceless Lesson In Real Risk

From fleecing Chinese Players to being fleeced - The Ludic Fallacy - Avoiding being a sucker - The only certainty is uncertainty

On February 27th 2019, I received a text saying, “Hey Jason, all our funds just got confiscated, and they’ve accused us of collusion.”

Between the 10 of us, the amount confiscated was just shy of £1 million.

This was the day I felt the wrath of true real-world risk and finally understood what it meant.

To understand how I got to this point, we must rewind a few years to May 2016.

At the time, I was playing a lot of live poker in London, i.e. playing poker in casinos. My lifestyle was terrible. I played poker from 9 til 5, that is, PM to AM. I ate like shit, never worked out and barely ever saw sunlight. At one point, a friend asked if everything was okay because I looked like I had been taking too many ‘extracurriculars’ — I hadn’t.

I wanted to transition back into online poker to have a healthier lifestyle, but the money was too damn good playing live. Until one day in early May, an opportunity presented itself. I was invited to play in these Chinese online poker exclusive clubs. What some of you may not know is that Chinese people are notorious for gambling, and they gamble badly, too.

These online poker games were mobile-based apps. It goes without saying that these poker apps were shady as hell. There were no government regulations, know-your-customer process or proof of residency and identity involved. All you needed was a phone number and some Bitcoin to deposit.

However, if I wanted access to these games, I had to get staked. Meaning a backer (in this case, the person who approached me) would put me in the games and in return, I’d give up 50-70% of my profits depending on the club or stakes I was playing. There were also middlemen — club agents who handled our deposits, withdrawals and P&L spreadsheets.

Everything had to go through them, all while taking a cut of the rake (a small commission fee taken from each pot played) I generated.

It was high risk, high reward. But this was an opportunity to return to a normal life, see some sunlight and stop looking like I had snorted enough ‘extracurriculars’ to wake a dead horse. So I signed my soul away. Matthew1, my backer, sent over four iPads, with the login details and loaded the accounts with money.

If we were in the black and wanted our cut, we’d tell Matthew, and he would request the agent to withdraw from our accounts and send us either crypto or fiat currency.

Matthew formed a group of us to play in these games. Some people in the group were only allowed to play small to mid-stakes. Others could play high stakes, and a few could play the ultra nosebleed high-stakes games that ran. I was starting off at mid-stakes. For a while, each of us didn’t know each other's identities in order to avoid the possibility of collusion.

After a few years of crushing these games, playing on Chinese apps no longer felt risky. The agents would always be good for the money and even cashed us out quickly. We managed to develop a good relationship with some of them. The smarter ones understood that by not fee gouging us, they’d stand to benefit more in the long run if they gave us fairer terms. We were a constant source of income for them because of the sheer volume we put in.

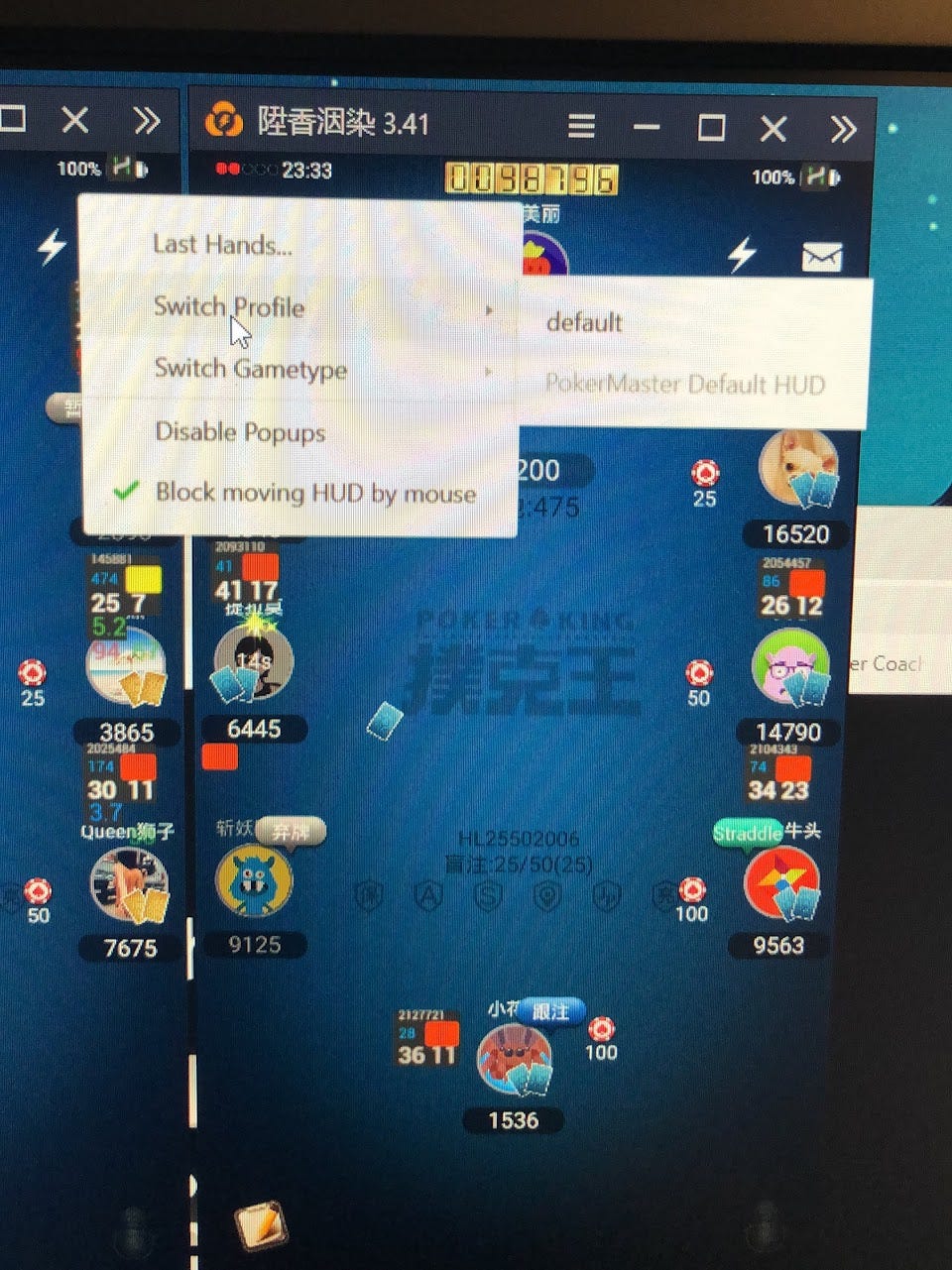

I had also managed to build a laptop powerful enough to emulate as many iPads as I wanted. This made playing on iPads obsolete. I had also discovered a heads-up-display (HUD) poker software designed for emulators, which recorded statistics on each player, further sharpening my edge to a point that was unethically unfair.

Matthew asked me to build and configure 9 more laptops for the other members of the group, at which point I learned all of their identities, and we were all added to a WhatsApp group.

At the beginning of 2019, a new app appeared called PokerKing. In the few years I had been playing on these apps, the games on PokerKing were the best I had ever come across. If you combined the soft poker games, my laptop and poker statistical software, what I now owned was a literal money printer.

It was so hard to lose. I could “wind down” at night by playing 1-2 tables of small stakes while watching a movie and win $200+ per hour without even thinking.

In early February 2019, a new player appeared at one of my tables. I quickly discovered that he was special. Most people on this site played poker without any brain cells, but this guy was a one of kind punter. Or, in poker lingo: a unicorn. Seriously, special was an understatement to this guy’s poker abilities. It was as if he didn’t know the rules or the hand rankings and gambled as hard as he could. Once he lost all of his money, he would then move up the stakes and repeat the same shenanigans there.

News of this unicorn quickly spread throughout the group, and we spent weeks chasing him across the various different tables and stakes. Even the weaker players on PokerKing were catching on to what we were doing and would try to sit down as quickly as possible whenever the unicorn appeared.

A one-hour session with the unicorn was almost a guaranteed minimum profit of $1000 per hour. With some back-of-the-napkin math, I had estimated that the unicorn was haemorrhaging somewhere between $25,000 to $50,000 a day.

Until one day, the unicorn disappeared.

A few days later, I received a message from Matthew informing us that PokerKing had accused us of two things: 1) botting and 2) colluding. PokerKing was freezing our accounts and investigating our agent and any of the accounts linked to him. In other words, our whole entire group was fucked.

Two weeks later PokerKing came back with a verdict which claimed we had used poker bots and colluded against the unicorn. We appealed, and they set up an ‘independent adjudicator’ to look over the evidence again.

But they came back with the same verdict: guilty.

The 10 of us had won just over ¥9 million RMB (£980,000/$1.25 million USD) within 3 months on PokerKing, with my gross winnings totalling just shy of ¥850,000 (~£92,500). Yet, we had become too trusting of these apps and didn’t cash out during the time we were all playing.

Just like that, almost £1 million evaporated overnight.

Casino risk is not real risk

I will never know the truth. A lot of the details are messy.

It is possible that our agent had a botting farm outside of our group. It is also possible that there was some collusion going on in the group. A hand played out between 2 members of the group in a suspicious way.

But also a month later, there were online reports from other players that PokerKing had confiscated their funds and accused them of the same thing. There were rumours going around that PokerKing were going after accounts with Western IP addresses.

The whole PokerKing affair taught me a valuable lesson in what real risk looks like: it’s never the thing you can see coming.

Let me explain. Poker is a game that deals with probability and random luck. Because of that, professional poker players learn bankroll management to manage risk and ride out the variance so that we don’t go broke.

But in doing that, we commit what Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls the Ludic Fallacy. What this means is that we mistake the kind of uncertainty found in games for the uncertainty found in real life.

In Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder:

Ludic Fallacy: Mistaking the well-posed problems of mathematics and laboratory experiments for the ecologically complex real world. Includes mistaking the randomness in casinos for that in real life.

As I found out, when we make that mistake, the consequences are disastrous.

It’s because the ideas and notions poker players had about uncertainty and risk are confined to a domain with rules that govern the game of poker. I could tell you about the Kelly criterion, bankroll management, game theory, solvers, frequencies, ranges, expected value, pot odds, probabilities, statistics, positioning, and player reads, all to make better decisions under uncertainty. But what I had failed to comprehend was that the real risk to my poker career and bankroll had nothing to do with charts, spreadsheets and understanding probabilty. The real risk existed outside the poker table. It existed in the real world.

Taleb says there are two domains in which we can think about risk:

Ludic: Set up like a game, and the rules are clearly defined like a casino.

Ecological (real life): No one knows the rules, and you can’t determine what variables contribute to what results.

Ludic is clear. Ecological is messy.

Poker is the domain of the ludic. I know what the rules are, and I can easily figure out pot odds and percentages with maths. It feels like I’m operating in a world of uncertainty when in fact, it is sterile. Business is ecological. I cannot calculate the odds of success. I can only know and learn as I go, and there’s much that I don’t know.

This is the point I want to highlight about risk-taking: Real risk is always the thing you can never see coming. You can’t forecast it in any of your models. If you could, it wouldn’t be a risk.

I failed to forecast that the creators of a poker app could get greedy and rug-pull me or that people I’m associated with could act so stupidly.

Understanding this idea can stop you from making a mistake and being a sucker. Taleb highlights this idea in his book, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, with a thought experiment. It involves two characters from his book — the street-smart “Fat Tony” and the intellectual yet idiot, Dr. John:

NNT (Taleb): Assume that a coin is fair, i.e., has an equal probability of coming up heads or tails when flipped. I flip it ninety-nine times and get heads each time. What are the odds of my getting tails on my next throw?

Dr. John: Trivial question. One half, of course, since you are assuming 50 percent odds for each and independence between draws.

NNT: What do you say, Tony?

Fat Tony: I’d say no more than 1 percent, of course.

NNT: Why so? I gave you the initial assumption of a fair coin, meaning that it was 50 percent either way.

Fat Tony: You are either full of crap or a pure sucker to buy that “50 pehcent” business. The coin gotta be loaded. It can’t be a fair game. (Translation: It is far more likely that your assumptions about the fairness are wrong than the coin delivering ninety-nine heads in ninety-nine throws.)

NNT: But Dr. John said 50 percent.

Fat Tony (whispering in my ear): I know these guys with the nerd examples from the bank days. They think way too slow. And they are too commoditized. You can take them for a ride.

Dr John is a sucker. I, too, was a sucker.

It’s only moving from poker to business did I realise that domain-specific games don’t actually train you for the real world. It can give you a slightly better map, but remember: the map is not the territory.

Your worldview, or the assumptions you make, may be entirely wrong. I’ve seen this play out many times at my bouldering centre. Hench gym-bros will strut into the centre thinking that they have the strength to climb anything, only for them to be quickly humbled 5 minutes later when they realise there’s a lot more skill involved when it comes to functional real-world strength.

Don’t be so quick to make assumptions. Chances are the frame of assumptions you make is wrong. So ask more questions and spend time thinking about potential consequences. In the case of Taleb’s thought experiment, the first question you should ask is, is the coin really fair? Or if you win, do you get paid in cash? And how do you know you haven’t been set up for a mugging when you leave the building? (This recently happened to someone on Reddit as they were leaving the casino).

Of course, you can’t come up with all of the questions you could ask about risk. After all, you don’t know what you don’t know, but that doesn’t stop you from asking the ones that come to mind.

“But Jason, I don’t take risks! Why does this matter to me?” I hear you ask.

It matters because the only certainty in life is uncertainty. Understanding risk and decision-making is how you stay adaptable to change.

I leave you with a quote by Pema Chödrön:

“The truth is that we’re always in some kind of in-between state, always in process. We never fully arrive. When we’re present with the dynamic quality of our lives, we’re also present with impermanence, uncertainty, and change. If we can stay present, then we might finally get that there’s no security or certainty in the objects of our pleasure or the objects of our pain, no security or certainty in winning or losing, in compliments or criticism, in good reputation or bad—no security or certainty ever in anything that’s fleeting, that’s subject to change.”

— Jason Vu Nguyen

Name changed for obvious reasons