Hey Friends,

Growing up, I discovered how much torment and frustration I could bring a person with just one word.

Why?

I questioned almost everything my mother made me do. Understanding why I had to do something was important.

But often, I was met with the reply, “Because I said so!” Unsatisfied with this answer, I would continue doing it my way until the feather duster came out.

Asides from frustrating my mother, I know from behavioural science acquiring some understanding of why we do things is often a prerequisite to behaviour change. This is especially needed when we think about the bad habits we want to break. Why do I smoke every hour? Why do I drink til I black out every weekend? Why do I struggle to exercise?

Yet, the reasons for what we do and how we live are often obscure. We imagine that our behaviour is, for the most part, a matter of conscious choice. But neuroscience and psychology show us it isn’t so.

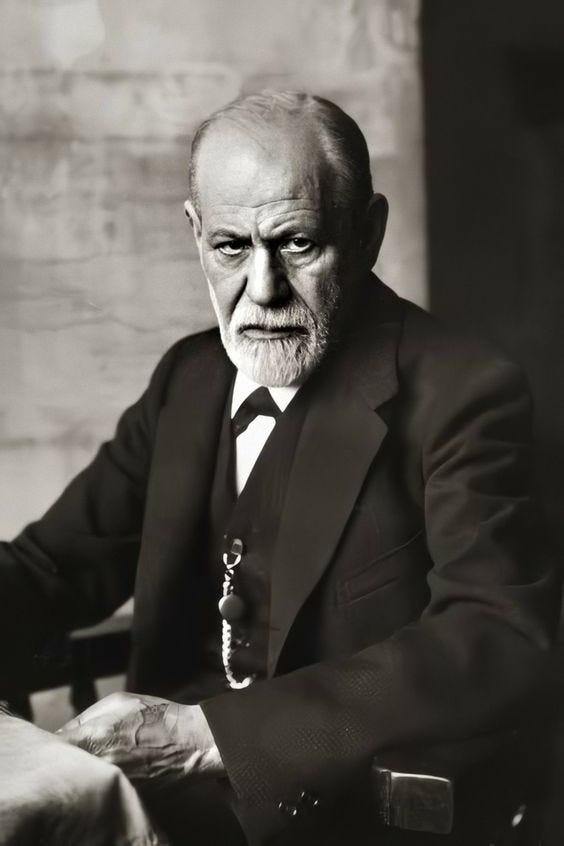

Although some of his ideas are a bit deranged, Sigmund Freud’s major contribution to psychology was the theory of the unconscious mind. Our minds function below the level of our conscious awareness and largely influence our behaviour.

For many people, the idea that much of what we do is the result of hidden motives is terrifying. It implies that we have no control over ourselves. This is where the term ‘Freudian Slip’ comes from — an unintentional error regarded as revealing subconscious feelings. For example, calling a partner by your ex’s name.

However, it’s one of those weird life paradoxes. It’s only when we acknowledge that in the depths of our consciousness exists a swamp of repressed desires and motivations that affect our day-to-day behaviour, do we make a step towards self-understanding and self-awareness.

If we deny the ugliness of our inner life, it leads to troubling results: Destructive patterns of behaviour in which we repeatedly make the same mistakes.

To begin to change our maladaptive behaviours, we must first recognise the patterns and ask why are we behaving in a way that is detrimental to ourselves. This is really uncomfortable to do. It’s always easier to resist and blame others than take responsibility for our shortcomings.

As they say, old habits die hard. We’re fearful of change. We’d rather play it safe. Even I’m not immune to being risk-averse. Particularly in activities that involve rejection, I know I can act in a way as if my sense of self is fragile and must be at all costs protected.

I used to believe my fears and insecurities would magically disappear with age and experience. But they don’t unless I work on them and put myself out there.

Venturing into the unknown and doing new things is hard. Because when presented with opportunities, we frequently defend ourselves by asking “Why?” first. This leads to an endless list of excuses for not taking a chance.

“I’m not good enough.”

“I don’t have time.”

“Everyone on dating apps is boring.”

If people are reluctant to answer “Why?” they tend to have even more trouble with “Why not?” as the latter implies risk.

Whenever I meet someone who is extremely risk-averse, I often ask, “What is the biggest risk you’ve ever taken?” The question does two things. First, it gets them to think about their life. And second, it allows me to try and understand why people live such “safe” lives.

I know some of the things I do – bouldering, travelling, writing, poker, triathlon, starting a business – are foreign to most. But I think something in our soul is lost when we obsess over safety and security – some spirit of adventure and fulfilment.

Life is one long series of gambles. First, the odds of you being born is 1 in 400 trillion (that’s how rare you are). On top of that, you don’t get a choice in what hand you’re dealt. Some of us get dealt a shit hand. Some a pair of Aces. But I believe we’re obligated to play the hand to the best of our ability. That doesn’t mean you will win or be the best. But that you will try your best.

Despite my predisposition towards risk-taking, as I mentioned earlier, I’m risk-averse in domains where it involves rejection. For instance, dating. Which I’ve started doing again.

Truthfully, it’s been scary. I don’t like being vulnerable. But after going on a string of many dates with one person, I realise that the highest stakes game we play in our lives is not in business or careers, but the one with our hearts.

There’s no manual guide on how to love. Sure, we can extract all we can from our parents. But knowing and doing are two separate things. The doing part of love, from a rationality lens, is inherently risky.

So how do we balance the risk of making a catastrophic psychological mistake versus the certainty of aloneness if we play it safe? Nowhere in our lives do cynicism on the one hand and foolhardiness on the other seem so dangerously high stakes.

This is where we must set aside our rationality lens and have faith.

Because in order to love, we have to accept the fact we aren’t skilful at the start and that there is a steep learning curve accompanied by many painful mistakes before we become adept. It’s by having faith in our efforts that we will find someone worthy of our love.

To refuse and to protect our hearts against all loss is an act of despair.

To take the risk to be vulnerable and bare your soul in the face of rejection is an act of courage.

— Jason Vu Nguyen