The Narrative Fallacy

How narratives can distort our perception of reality and what to do against it

Hey friends,

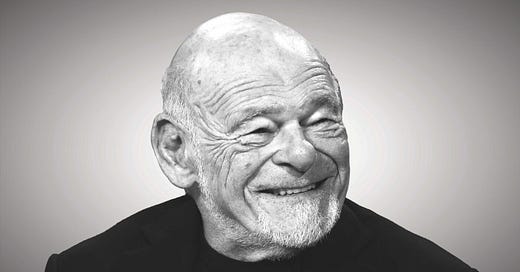

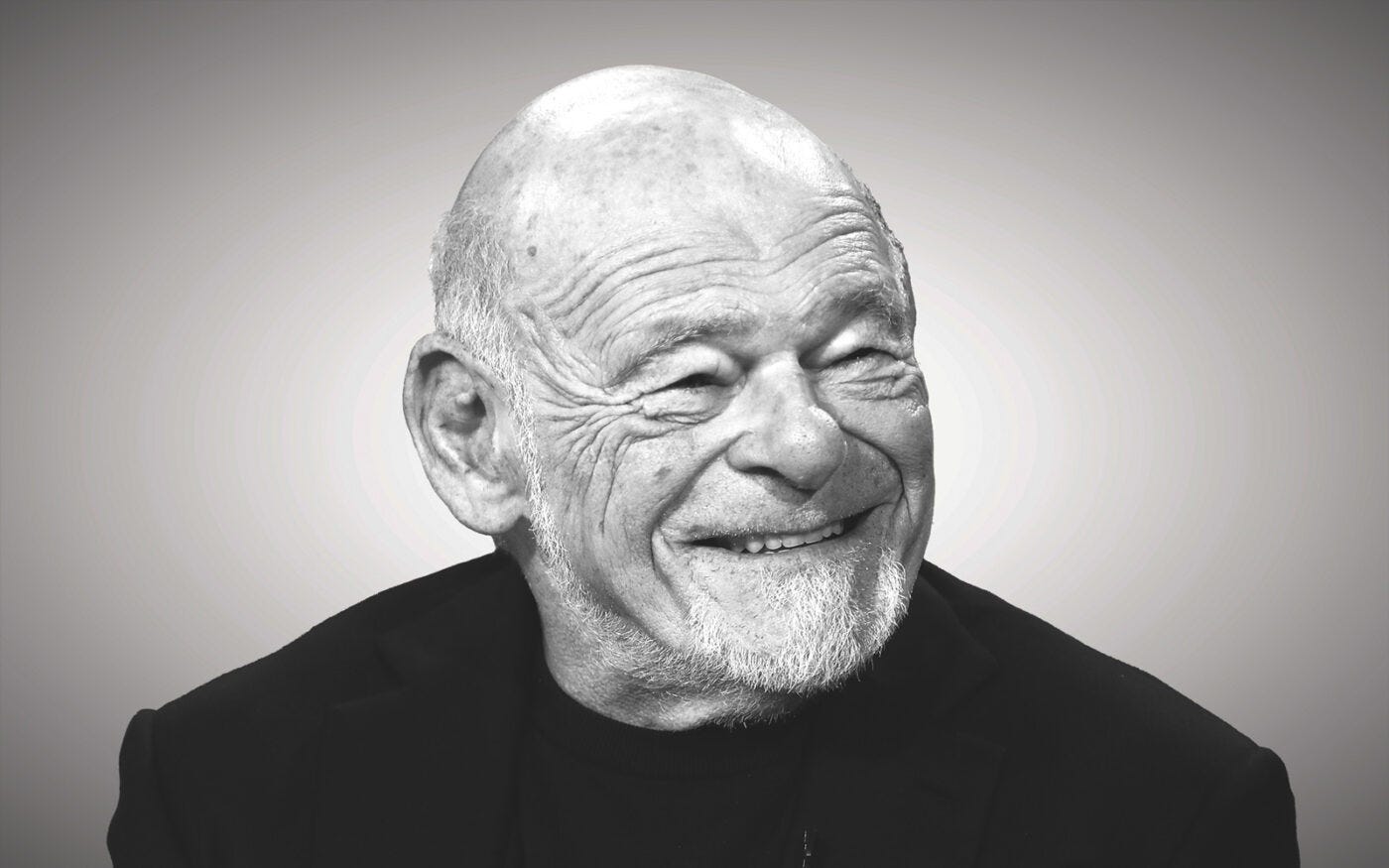

I recently finished Am I Being Too Subtle? Straight Talk From A Business Rebel — the autobiography of the legendary real estate investor Sam Zell.

For those who don’t know who Zell is, allow me to give you the 19-second biography:

Zell is an iconic figure in the American real estate industry.

Over his lifetime, he amassed a $5.2 billion fortune.

He is known as “The Grave Dancer” due to his ability to revive properties and projects at death's door.

He created Equity Group Investments to invest in properties – controlling a billion-dollar investment portfolio.

He helped create the real estate investment trust (REIT) industry, and his team has IPO’d some of the world’s largest publicly traded REITs.

Zell’s story resonated with me.

Not in the way where I’ve amassed a billion-dollar fortune. But in the fact that we’re both first-generation immigrants belonging to war refugee parents, mischievous in nature, have this embedded sense of urgency, a desire to understand risk, a tendency to go left when everyone is looking right, and we blur the lines between work and play.

Here’s an excerpt from the first chapter:

“My father was the first person I knew who had done something “impossible.”

At thirty-four, he escaped his hometown in Poland on the last train out, just hours before the Luftwaffe bombed the tracks, and then led my mother and two-year-old sister on a twenty-one-month trek across two continents to safety.

As a result, I grew up believing that anything is possible. And when you’re not aware there are any limitations, nothing stops you from trying.”

My story echoes that of Zell’s. At a young age, my parents escaped Vietnam before the fall of Saigon and trekked across two continents to safety and made the UK their home.

Growing up and seeing my parents start two successful businesses, buy their house outright, give my brothers and me a good education, make sure there was always plenty of food to eat, and set us up to succeed, I, like Zell, grew up believing that anything is possible.

Seeing the parallels in mine and Zell’s life makes me feel like I’m practically destined for business success. These types of founder stories strike a deep chord with me. It gives me a way to make sense of my own life and leads me to believe that I can predict my future.

But the ultimate power we humans possess is also our biggest downfall. This is me falling prey to the narrative bias and attributing any success I’ve achieved so far to my background.

I’ve read enough of these business biographies, and they often start in a similar way. They describe the early years of a founder in order to illustrate the founder’s success was determined in their childhood.

By looking backwards, we set off a mental tripwire that causes us to develop a linear narrative with a clear cause-and-effect sequence.

But the harsh truth is that it’s all largely bullshit. Life is complex, and we’re being fooled by randomness.

It’s easy for me to say my parents inspiring intelligence, curiosity, and hard work into me led me to do well in poker. And while that may be true, I know a lot of it came from luck and timing. I was with the right people, in the right place and at the right time.

The reason why we construct narratives is that we are bombarded with so much information that our brains have no other choice but to put things in a linear structure in order to process the world around us.

The world is fuzzy and complex, and narratives (this includes: novels, stories, myths, anecdotes and tales) simplify reality by compressing information in order to fit inside of our heads.

Taleb explains in The Black Swan:

Consider a collection of words glued together to constitute a 500-page book. If the words are purely random, picked up from the dictionary in a totally unpredictable way, you will not be able to summarise, transfer, or reduce the dimensions of that book without losing something significant from it.

You need 100,000 words to carry the exact message of a random 100,000 words with you on your next trip to Siberia. Now consider the opposite: a book filled with the repetition of the following sentence: ‘The chairman of [insert here your company name] is a lucky fellow who happened to be in the right place at the right time and claims credit for the company’s success, without making a single allowance for luck,’ running ten times per page for 500 pages.

The entire book can be accurately compressed, as I have just done, into 34 words (out of 100,000); you could reproduce it with total fidelity out of such a kernel. By finding the pattern, the logic of the series, you no longer need to memorise it all. You just store the pattern. And, as you can see here, a pattern is obviously more compact than raw information. You looked into the book and found a rule.

The more random the information is, the greater the dimensionality. As a result, it is more difficult to summarise. But the more you summarise, the more order you impose, the less randomness you’re made to feel. This is where the narrative bias can wreak havoc in our perceptions of reality.

As someone who is drawn to professions riddled with high randomness (poker, investing and business), I’ve witnessed first-hand how we fall for the bias time and time again: I should have folded my hand; I knew I should have called my small pocket pair and hit my set; I bought bitcoin in 2014 and sold it for some drugs. If only I held on to it!; et cetra.

Yeah, but you didn’t. This is the narrative fallacy (plus a nice dose of hindsight bias) weaving an explanation in your head to help you make more sense of the world.

6 Defence Tactics Against Narratives

So, if the attempt to distil the complexity of life into easy narratives is dangerous, what can we do about it?

Well, in the same way where a diamond can only cut a diamond, stories can only displace other stories.

The first step is to become a better storyteller and understand the mechanics of storytelling, which I wrote about here.

The second step to avoid the ills of narrative bias is to become aware of the bias and understand when it exists. It’s realising that you’re susceptible to this way of thinking and exposing your views and beliefs to more analysis.

The third step is to always ask yourself these two questions:

Out of all the people who followed the same steps, how many succeeded like the hero of the story?

What hard-to-measure causes might have played a role?

Be very wary of anyone who sells you success in 5 simple steps or promises you a money printer.

The thread was too long. You can read the rest of it here.

Be careful of narratives like this. They sell you on the idea that all you have to do is deep work, and money will begin to fall from the sky.

First, we must ask ourselves: How many people have tried deep work and earned a $1M/year business? Vs How many people have tried deep work and failed to earn any money? (I suspect the latter vastly outweighs the former.)

What other hard-to-measure factors are at play here?

I’m not trying to shit on deep work, in fact, I use it myself. But success is not as clear-cut as people make it out to be. Luck and timing play a big role in a person’s success.

The fifth way to defend yourself against narratives is to be careful of people who are talented at painting a narrative. All marketers, salespeople, consultants and writers would fall into this category. Yes, this includes me too.

A good narrative is so powerful that it can override basic logic.

Lastly, the sixth way comes from Taleb himself:

When searching for real truth, favor experimentation over storytelling (data over anecdote), favor experience over history (which can be cherry-picked), and favor clinical knowledge over grand theories. Figure out what you know and what’s a guess, and be intellectually honest.

I’d place great emphasis on being intellectually honest.

As the physicist Richard Feynman once said, “The first principle is not to fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.”

— Jason Vu Nguyen

📚 What I’ve Been Reading This Week

Lately, I’ve been sharing what I read with my close friends on Instagram, which they all seemed to like.

So, I figured I’d also share with you guys too.

📘 Books:

100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Currently 2/3 of the way through it. The genre is magical realism. It’s an interesting writing style and a chaotic read. However, I’m starting to grasp the plot and the repetition and themes. Very beautiful poetic writing.

Quote:

“What does he say?' he asked.

'He’s very sad,’ Úrsula answered, ‘because he thinks that you’re going to die.'

'Tell him,' the colonel said, smiling, 'that a person doesn’t die when he should but when he can.”

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

I love this book. In fact, I love the whole Incerto series by Taleb. This is my second re-read, and I missed so many things the first time around. This is the OG guide to understanding how risk works in the real world.

Quote:

“The problem with experts is that they do not know what they do not know.”

📑 Articles:

How to Do Great Work by Paul Graham — for those who want are ambitious and want to find their calling in life. It is a long read but worth it. I’ve practically highlighted the whole article.

The boardroom drama behind Gymshark, one of the UK's fastest-growing companies by Andrew Lynch — I’ve mentioned Andrew before, but he’s been getting better and better every week. Part 2 came out today!

Proof You Can Do Hard Things by Nat Eliason — As someone who bounced back from low-self esteem issues, proving to myself that I could do hard things played a pivotal row in increasing my confidence. This is a great read if you need to know why you need to do hard things.