Playing Russian Roulette

How understanding this morbid game can improve your decision making in life, health and business.

I don’t know what’s been happening or where I’ve been shared but welcome the 37 new subscribers!

Last week, I wrote about the beginnings of Stoicism. If you missed it, you could read that article here.

Today we’re talking about how to think about risk, Ergodicity and survival.

*gasp*

You open your eyes.

It’s dark. You look around. The room is dimly lit. You see 5 other human silhouettes.

Your head is pounding, like you’ve been pistol-whipped.

Groaning, you try to remember what happened.

But it’s no use; your mind is too foggy.

You hear a sound in the distance.

Tap… Tap… Tap…

You freeze as you recognise the sound — Footsteps.

And they’re getting closer.

Your blood runs cold as they stop right outside the door.

The door opens, and you can see a male figure walk in…

He flicks on the light.

You wince and cover your eyes to block the light from scorching your corneas.

You get a good look at your perpetrator.

He’s 5ft 9, Asian and with slick back hair. He’s wearing slim-fit black trousers and a light blue oxford shirt.

Not quite what you were expecting for a villain.

Allow me to introduce myself. My name is Jason Nguyen…

And all 6 of you are now my prisoners.

Because I’m feeling a little sadistic today, we’re going to play a little interesting decision-making game.

That game is called Russian Roulette.

You may have heard of it before, or you may not. The rules of the game are simple.

You and the five other players are each given a gun.

I want you to point the gun to your head and pull the trigger.

What’s that? I’m crazy, and you will never play Russian Roulette?

Well, how about I make it interesting…

If you pull the trigger and survive, I’ll give you $6 million.

You gasp and mutter, “No…”

Think about it. Either stay as my prisoner. Or you can play, win, and leave here a free soul with six million dollars. Imagine what you can do with all that money…

Come on. You know there are 6 chambers in a pistol. That means you have a 1 in 6 chance of dying and a 5 in 6 chance of surviving.

That’s some pretty sweet odds, aye?

You look around at the other 5 people in the room.

I know you want to play. After all, 5 out of 6 Russian Roulette players recommend the game…

I see the degenerate sparkle in your eyes and pull out six pistols.

You mutter to yourself as you pick up the gun, “What on earth am I doing….”

You point the pistol to your head and…

Click!

Phew. You survived…

I walk over to you.

“Oh shit, he’s coming for me,” you think to yourself.

I smile and pull you towards me.

How about we change the game a little? Would you like to play Russian Roulette six times in a row?

Think of all that money you could win….

$36 million…

As tempting as $36 million is, we intuitively know that the more times we play, we will for sure be dead. It’s not like we can take the money with us into the afterlife, either.

I know the thought experiment is a bit extreme, but the game of Russian Roulette highlights how to think about decisions: The outcome for an individual is different from that of a group. And the average of the group tells you very little about the individual experience.

Just like in Russian Roulette, humans can be terrible at judging odds. And they apply the same mistakes to other areas of their life — such as relationships, careers or investing — often leading to disastrous consequences.

In Russian Roulette, one loss means you die. Because death is irreversible, this extends into the future, and you cease to win any more money.

The concept of irreversibility is counterintuitive and goes against what we learned in school: averages matter. But this is often wrong.

Be Careful of Averages

“Don’t cross a river if it is four feet deep on average.” — Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

If you flip a coin (assuming it’s fair) 1000 times, on average, it will come out 50% heads and 50% tails.

If 1000 people flip a coin once, on average, the results will be 50% heads and 50% tails.

Coin flipping is what we would call an ergodic system — the time average is equal to the ensemble average.

However, in Russian Roulette, it is non-ergodic: the outcome you get by playing it 6 times in a row is different to the average outcome of 6 people playing it once.

Let’s say that 6 people play Roulette once each. On average, 1 person will die, and 5 will win $6 million each. The total winnings as a whole are (5x$6 million) $30 million. Divide by the number of participants, in this case, 6, and that makes $5 million as the expected outcome. In other words, if we played Russian Roulette a bunch of times, each person, on average, is expected to win $ 5 million.

This expected value remains true even if we add more players to the game.

Let’s say 600 people decided they wanted to play. On average, we will have 100 deaths (remember, there is a 1 in 6 chance of dying). The total winnings paid out will be $ 3 billion. Divide by 600 people, and you still get $5 million as the expected outcome.

The expected outcome is also called the population outcome.

Now let’s work out the average outcome for when you play Russian Roulette on your own 6 times in a row.

Your individual expected outcome if you play Russian Roulette is also a 1 in 6 chance of death and an expected outcome of $5 million. However, if you play it more than once, it begins to decrease. If you play this game infinitely, you guarantee your demise.

See how averages can be deceiving?

The chart shows your expected financial gains from playing Russian Roulette many times. This is measured across one person and many repetitions. The term for this is time average outcome.

If the population outcome is the same as the time average outcome, we can say the system is ergodic. Otherwise, it’s non-ergodic.

I know that was a bit boring and technical, and you’re thinking, what’s the point of it all?

Well, in ergodic systems, you can use averages to make optimal decisions. In non-ergodic systems, you can’t.

Understanding this teaches you how to think about risk-taking.

Game Over

In Russian Roulette, if you die, you won’t be able to pull any more triggers. In other words: it’s game over. Your future earnings effectively become $0.00.

Anything that has the possibility of game-overs is a cause of non-ergodic systems.

These game-over situations are more common than you think. For example, they include bankruptcies, injuries, severe depression, burnouts or breakups (romantic, business and friends).

Alright, so some of you may be thinking, “I’m risk averse; I won’t let this happen. Why should I even care about Russian Roulette?”

The thing is, much of life follows a similar dynamic to Russian Roulette, in which ruinous losses absorb all future gains.

Let’s take my favourite sport, bouldering, for example. The harder I climb, the faster I progress. However, if I go too hard, I may irreversibly injure myself, for example, breaking my spine from falling off the wall. The irreversible damage to my spine will end my ability to exercise.

Another example is careers. The harder you work, the more opportunities you create for career success. However, working too many long hours may damage your health, relationship or sanity. Once lost, it’s hard to recover from.

When it comes to making risky decisions, you want to avoid the single negative event that can undo all of your efforts.

I love the risk of climbing, yet I will never make an uncomfortable move that can cause a catastrophic injury which can undo all of my fitness and climbing efforts.

It’s Not About Being The Best

It’s about being the best of those who survive.

In theory, performance determines success. The highest-performing employee becomes the most successful one.

In practice, performance is subordinate to survival. It is the highest performing employee who doesn’t burn out that becomes the most successful one.

The same idea applies to investing, business, relationships and so on. Survival matters more than performance. The idea of business isn’t to win; it’s to keep doing business for as long as you can. The goal of marriage isn’t to win; it’s to stay married.

In the short term, consequences that apply beyond the short term don’t matter. But over the long term, they do.

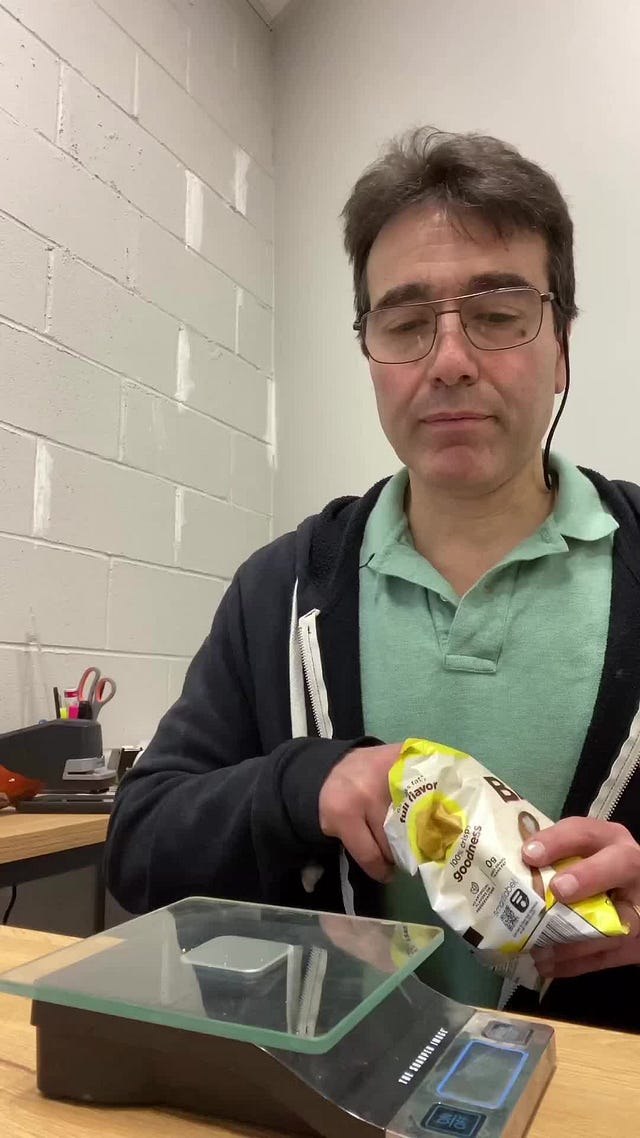

This TikTok video perfectly highlights my point.

In the short term, each potato chip weighing 0 grams doesn’t matter. But as hilarious as the video is, we all know that given enough time and potato chips, the results will be many inches added to our waistline.

Burnout at work is another example and is often a phantom consequence of working too hard. It’s not observable in the short term but affects the long term. Smoking is the same. The daily observation seems like it’s nothing, but in the long term, it leads to serious long-term damage.

In non-ergodic systems, you need to consider the impact of irreversible consequences.

You also don’t want to maximise growth regardless of survival. Instead, you want to maximise growth while conserving survival.

Risk Taking

Many of you know I am a risk taker: poker, business, investing, etc.

I see the same lesson being reiterated in these domains of uncertainty: “In order to succeed, you must first survive.”

That means at all costs avoiding the risk of ruin.

I don’t mean to imply you shouldn’t take risks, but to highlight that in any strategy that entails ruin, the benefits will never offset the risks of ruin.

For the purposes of this article, the concept of Ergodicity has been explained in a more accessible way. The essence of the article is correct in its practical meaning but technically imprecise.