I have two interests that are quite different but, in many ways, are quite similar: The stock market and advertising.

They both aim to seek a return on investment (ROI).

How does an investor know how much of their fund to invest in a particular stock?

How do media buyers allocate the right resources for which advertising medium?

Both disciplines demand answers where it’s hard to tell which decision is the right move to make.

A lot of poker is like this. What’s the right strategy in this scenario? How much do I bet to ensure sure my opponent calls but also maximises my earnings? Often, my approach was to use game theory to answer these types of questions.

What is game theory? Well, it’s a study of situations where the best choice (or strategy) amongst alternatives depends on the choices others make.

Not all situations are like this. For instance, choosing what to have for breakfast, unless you’re a mother and your 5-year-old child wants Oreos for breakfast, other people don’t care what you pick.

However, often in the real world, our choices are interdependent. For example, in football, a penalty taker has to choose whether to kick the ball left, right or straight down the middle of the goal, depending on what direction he thinks the goalkeeper will dive in.

Economic situations often have the same characteristics – a business choosing to undercut a competitor by reducing the prices of its products to achieve more market share.

Game theory analyses these situations using a concept called Nash equilibrium (named after the Nobel prize winner John Nash). When a situation has achieved nash equilibrium, it has reached a stable condition when all participants are making the best choices they can.

Game theory underpins much of modern microeconomics. And it’s a useful mental model to help think about interdependent choices.

I’m all in Mr Bond

Game theory is a natural fit for poker since the choice of when and how much to bet depends on what cards I’m playing, what my opponent has, and how they plan to play their hand.

The conceptual father of game theory, Jon Von Neumman, tried applying it to poker in 1944 but failed. Over the next 65 years, poker players ignored game theory. Sure, they had a basic understanding of odds and probabilities, but generally, they relied on rules of thumb (heuristics) to make decisions.

The best players had a good “feel” for the game. They’d intuit body language, table dynamics, psychology and other intangible knowledge. Or as James Bond says in the 2006 film Casino Royale: “In poker, you never play your hand. You play the man across from you.” (For those into poker, given the action, Le Chiffre could have folded his hand against Bond).

A brief history of poker

To understand how things started to change in poker, we have to go back to 2003, the birth of modern poker.

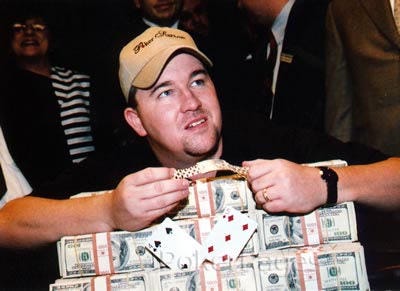

The aptly named Chris Moneymaker, an accountant from Atlanta, Georgia, won the World Series of Poker (WSOP) Main Event in Las Vegas. WSOP is kind of like the Olympics but for poker.

Moneymaker’s win revolutionised poker because he was the first person to become a world champion after qualifying from an online poker site for $39. There he gained entry into the $10,000 WSOP main event and went on to win $2.5 million. Dubbed the ‘Moneymaker effect’, his win helped sell poker as a spectator sport.

Following Moneymaker’s success, TV poker rapidly grew in popularity. Viewers could see the cards dealt to each player. Within four years, poker became the third most watched “sport” on US television. The growth in popularity also boosted the number of WSOP entrants, increasing from 839 in 2003 to 8773 in 2006. These numbers have held constant since then — in 2022, there were 8663 entries in the WSOP main event.

Launched in the late 1990s, online poker enjoyed a similar boom. Major online sports betting businesses diversified into poker, with the most popular sites drawing in hundreds of thousands of visitors per day. Poker’s sudden popularity attracted new players to the game, and with that, an opportunity to make a living playing online poker full-time became possible.

The Old School vs The Internet Wizz Kids

Online poker created a divide between old-school poker players, who made their bread playing live poker in casinos, and the aggressive wizz kids of online poker.

Old-school players heavily relied on psychology and “playing the player.” Compared to the internet kids who based their strategy on maths, probabilities, and statistics.

Online poker was faster-paced than live poker. This allowed the internet kids to play more hands, experience more tough scenarios and use software (called heads-up-display (HUDS)) to track opponents.

In online poker, you could play thousands of hands a day, compared to the 25 hands per hour you were dealt in the casino. The advantage was clear as night and day.

The internet kids now took game theory seriously. In particular, the idea of nash equilibrium (which we refer to as Game Theory Optimal (GTO) strategies).

In poker, nash equilibrium is reached when all players choose strategies that maximise the money won given the strategy used by other players. If you could deploy GTO in poker, you would never lose money in the long run (once variance evened out over a large sample).

The idea behind GTO is that even if players could figure out your strategy, they couldn’t beat you – at best, breaking even because your strategy would be “unexploitable.”

Of course, it’s not enough to know that the perfect unexploitable strategy exists – you also need to know what it looks like. Even for the most powerful computers, finding nash equilibrium was unattainable – 1326 combinations of starting hands, 254,251,200 possible combinations of community cards and few restrictions on bet sizes. That was too much computing power for a machine to crunch through. Even heads-up matches (only two players allowed playing 1 vs 1) have around 10^160 hypothetical situations.

However, that didn’t mean game theory had nothing to offer. At first, we calculated game theory strategies using simplified models involving game trees and frequency calculators.

The Internet Wizz Kid 2.0

Then, as true to Moore’s law, personal computers became powerful enough for us to run game theory solvers. In 2015, the first game theory solver was released called PIOSolver.

It created a new evolution of internet wizz kids. One that was more aggressive, more precise and more unpredictable.

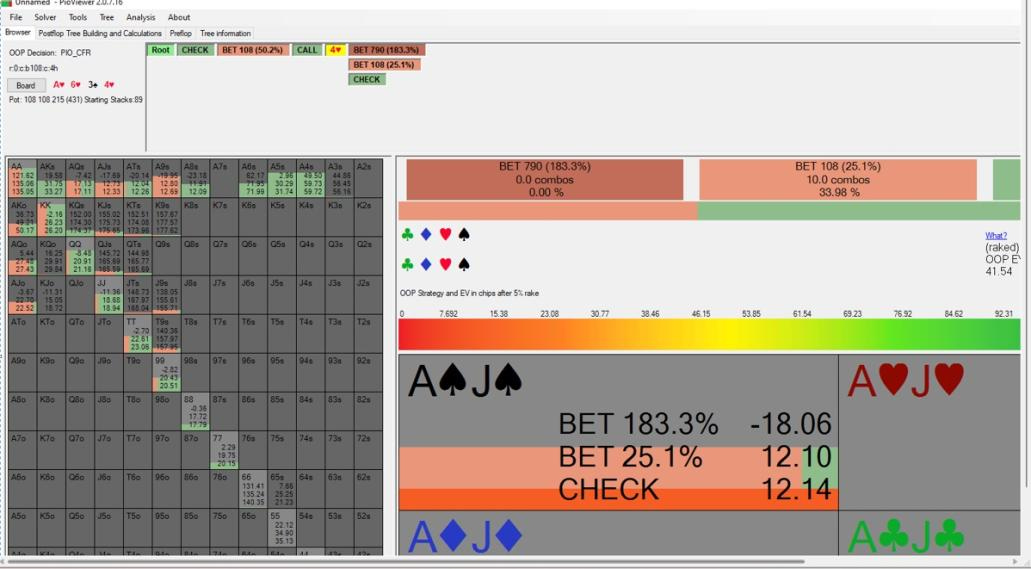

My professional career started in 2013, so solvers became infused into my strategy. We could now input opening ranges, different bet sizes, stack sizes, community cards and the range of hands our opponents could hold. The solver would crunch out the appropriate GTO strategy.

We spent hours looking for patterns and trying to reverse engineer the logic behind these strategies – how often we should be betting on what board textures, what hands we should be betting with, and what bet size yielded the highest expected value (the value you will get on average).

To speed up the process, we rented virtual computers running off Amazon web servers. This allowed solvers to crunch through all the data and spit out the strategy in days or weeks, depending on the complexity.

We would then sort the data and sift through spreadsheets looking for patterns (see below).

We were discovering new and nuanced strategies to dominate the game.

Live pros and weak online pros would mimic solver strategies without really understanding why. Which in turn left them exposed for good pros to exploit the gaps in their knowledge.

Those of us using solvers changed the game. Here are a few key changes that stood out:

More aggressive bluffing

The GTO strategies showed us we weren’t bluffing enough (betting with a weak hand).

So we started ramping up the bluffing aggression to maximise our expected value. We were seen as crazy and aggressive. Previously the old-school players thought they should bet mainly good hands and bluff only a little bit. The game theory solvers showed us this was wrong, particularly on earlier streets like preflop and flop.

Obviously, there’s nuance and context required, but in general, it was best to bluff like crazy because opponents were under-defending against a high-frequency bluff strategy.

The solvers showed us the optimal ratio of bluffs to value in which positions and which board textures.

The logic becomes threefold. First, bluffing more means your opponent will need to call your bets more often to stop you from winning with weak hands. Second, you now have the potential to win more money when you have a strong hand because your opponent is forced to call wider, weakening their range, to defend against you. Thirdly, hands you bluff (provided you select the right ones) can still improve and become a strong hand when the turn and river are dealt.

The solvers showed us that we could also size down our bets in the first few streets. This made the price of bluffing cheaper. As a result, against weak opponents, you could bluff a lot more for a lot less.

The aggression was relentless if you didn’t know how to fight back.

Mixed strategies

Game theory often recommends using mixed strategies – randomly deciding what to do with a given hand in some situations – to avoid becoming too predictable.

As the Vice Chairman of Ogilvy and Ad-man, Rory Sutherland, once said, “Being slightly bonkers can be a good negotiating strategy: being rational means you are predictable…..If you are wholly predictable, people learn to hack you.”

This was important for internet wizz kids because of tracking software. If opponents were using HUDs to analyse our play we needed to defend against it by being selectively random. Sounds paradoxical, I know, but we would use random number generators to determine which part of the strategy we would execute.

Short stack play in tournaments

I was never a tournament player, but I saw solvers revolutionising the field.

Tournaments were considered the softest form of poker because very few knew what they were doing. Solvers recommended when to go all in and when to fold. GTO players could maximise their expected value and avoid folding themselves to death.

As a result of PIOSolver and other solvers being released, poker players improved dramatically, to the point where it was difficult to beat the game consistently unless you had game theory knowledge.

Old school players made their money from an exploitative style, whereas the internet kids made their money on math-based strategy.

Today, if you don’t understand game theory in poker, you may as well hand over your money to the table and walk away. It’d save you time and headache.

The end of poker?

I left poker in August 2021.

One of the main reasons was that I felt the end was near.

In 2019, Facebook’s AI Lab and Carnegie Mellon University teamed up to build a poker bot called Pluribus to see if it could beat human players in multiplayer scenarios. Pluribus became "the first bot to beat humans in a complex multiplayer competition."

Despite the victory, the developers declined to release the source code out of fear it would be misused to cheat in online poker.

As noble as their intention was, it was futile. A year later, real-time assistance (RTA) solvers appeared on the scene.

Someone I knew on Telegram offered to show me how it worked. Curious to see how good it was, I accepted the private invitation.

Witnessing the RTA in action was the nail in the coffin for me. Soon everyone will be using one, and even if online poker sites find a way to ban RTA’s, someone will always find a way. The last I heard, you could run an RTA off an app on your phone.

As each day goes by in poker, as we get closer and closer to the Nash equilibrium of the game, there will be fewer opportunities to exploit people’s strategies. When this state is reached, poker players will, in theory, break even on their graphs but, in reality, lose to the rake that the house takes.

From Game Theory to Behavioural Economics

I know I talked a lot about game theory, but it isn’t the answer to everything.

Yes, it works well against tough opponents since GTO aims to maximise your winnings against opponents who are “rational”.

There’s a big debate in poker about whether you should play Game Theory or an exploitative strategy. An exploitative strategy involves a deviation from game theory which good players can exploit, leaving you vulnerable. But it can help you win more money against weaker players. And playing weak players is where 80% of your profit comes from.

It’s a stupid debate. The answer is: it’s both.

Having a 100% game theory strategy is being exactly like the proverbial man with a hammer — You see every problem as a nail. An overreliance on game theory can actually cause you to leave money on the table.

A good player starts with game theory as the basis of their knowledge but knows when to deviate towards an exploitative strategy given the right context. For instance, if you were sat at a table filled with all bad players, playing a game theory strategy is dumb because no one is good enough to exploit you back.

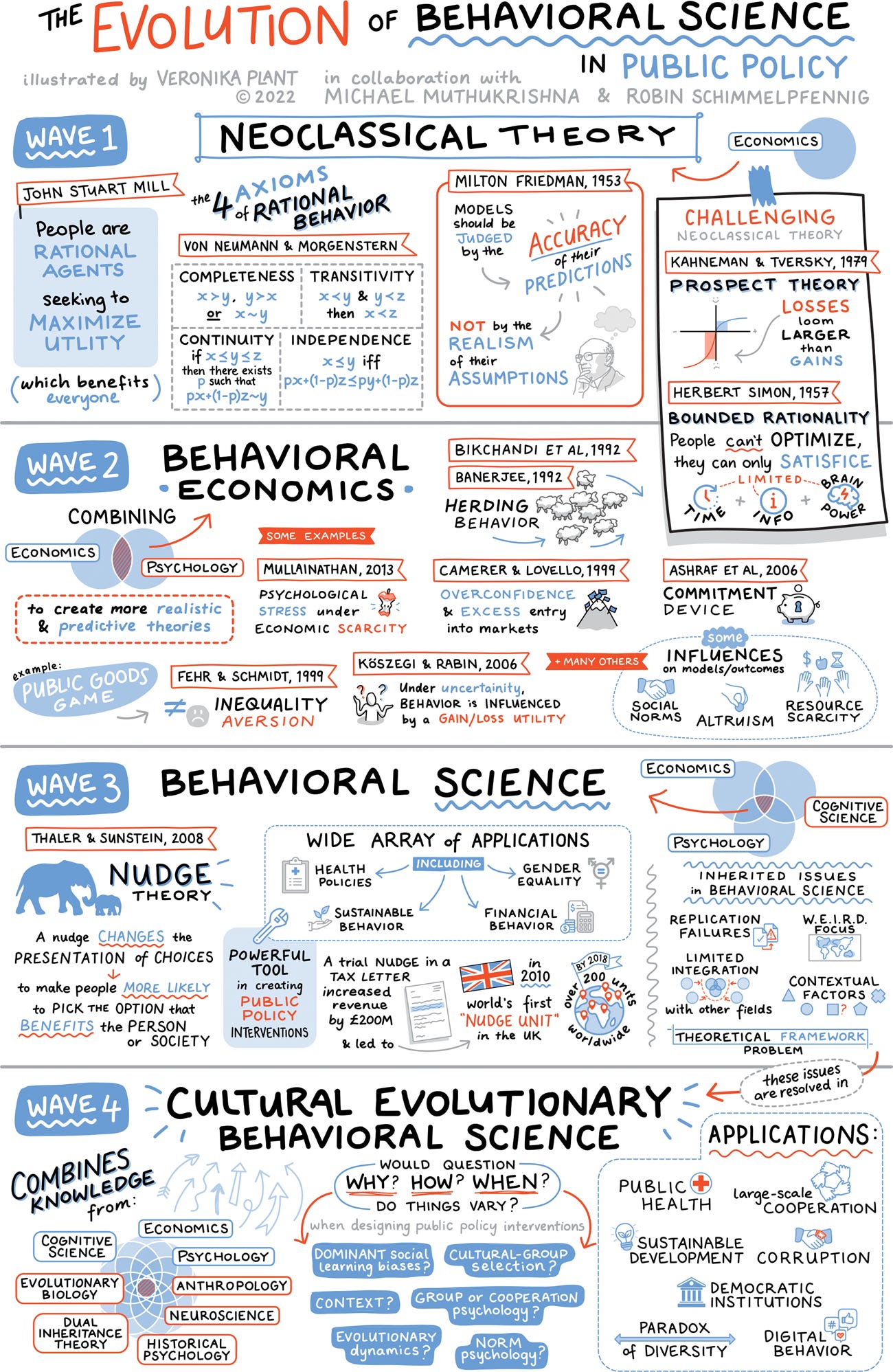

Just like how game theory assumes rational actors, traditional economic theory assumes that we always act rationally and logically. We don’t. We like to think we do, but we are driven by unconscious desires. We’re impulsive. We decide using heuristics which causes us to have biases.

Behavioural economics is the intersection of psychology and economics and is akin to the game theory and exploit strategy of poker.

Instead of assuming people behave logically and rationally. Behavioural economics models human behaviour through biases and heuristics. It looks at how people are actually behaving in a particular context. And explores why people sometimes make irrational decisions.

From years of watching people make decisions at the poker table, I never encountered anyone who could stay rational and logical 100% of the time. Even if they tried with every ounce of their body and soul, eventually, their emotions would take over.

Few people make decisions with a spreadsheet. Even economists, bankers and accountants struggle to make rational and logical decisions.

We decide with our emotions. We make them at the dinner table or in a board meeting. We decide with our personal history, unique view of the world, ego, marketing and incentives all mixed together.

We make the decisions that make the most sense to us at that point in time. Viewed through this mixed lens, some irrational decisions begin to make sense.

But none of it is crazy.

As the most important rule in behavioural science goes: context is everything.

Need help?

I offer insights into behavioural science, advertising and copywriting.

Contact me at hello@jasonvuvu.com