№ 68: In The End, It's All Behavioural

How I found behavioural science (BS) - A small primer on BS - Applying insights from poker to marketing and advertising

The hardest decision I’ve ever made was to leave my poker career.

There were a few reasons why it was so hard. The first reason was my identity was deeply tied to it, so this resulted in an identity crisis. The second, the money was good. And the third was that I thought I knew nothing apart from how to gamble.

Turns out that the last reason isn’t true. I tacitly understood things about decision-making (under uncertainty), but I just didn’t have the right vocabulary for it. In other words, I hadn’t yet found the world of behavioural economics and later behavioural science.

While scandals have rocked the industry lately, behavioural science has changed my personal and professional life in a meaningful way.

So, what is behavioural economics? Well, imagine if psychology and economics had a baby together, what you’d get is behavioural economics. Its purpose is to understand how and why people behave the way they do in the real world.

And how about behavioural science? First, I’ll give you the boring corporate-wiki-esque answer: “Behavioural scientists study when and why individuals engage in specific behaviours by experimentally examining the impact of factors such as conscious thoughts, motivation, social influences, contextual effects, and habits.” (Seriously, who writes these things).

My answer? It’s essentially social psychology rebranded to sound more intellectual for governments and big businesses.

In the end, it’s all behavioural.

“If economics isn't behavioural, I don't know what the hell is.” — Charlie Munger

Nudge — One deck at a time

On the 24th of July 2020, I received an investment pitch deck in my email inbox that nudged my life towards the field of behavioural economics.

Moneybox — an investing and savings fintech app — was doing a crowdfunding round. I had requested to see its pitch deck (not that I could understand it) to see if it was worth investing speculating some money on.

A wise woman once told me, “You need two friends in life: an accountant and a lawyer.” Fortunately, I had an accountant friend whom I asked to help me read through the financials of this deck. We, and I mean my friend, concluded that it wasn’t worth investing in. Its net income was deep in the red, and its future five-year projections were beyond delusional.

However, this led to me getting more curious about investing and the stock market. I read so many books on the topic: The Dhandho Investor, The Education of a Value Investor, Invested, One Up on Wall Street, The Little Book that Beats The Market, Rule #1, The Intelligent Investor, You Can Be A Stock Market Genius, Payback Time and The Incerto Series.

While I couldn’t yet fully understand the financials, I immediately understood how the psychology of the markets mirrored that of poker.

“Markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent” — John Maynard Keynes

When you enter the domain of the stock market, doing well has little to do with how smart you are and almost everything to do with how you behave.

This is also true in poker (and life too). No matter how awesome your poker strategy was, if you can’t stay disciplined and rational when luck is against you, you'll be broke in no time.

How you behave matters a lot. But behaviour is hard to teach, even to intelligent people (Note: this field is known as behavioural finance, a subsection of behavioural economics).

A YouTube Video That Changed Everything

At the beginning of 2021, I took up a free 1-hour consultation with a business coach named Erno Hannink.

I explained my backstory of being a poker player and my aspirations of becoming a Vietnamese coffee mogul. Erno suggested I check out a TED talk from an ad man named Rory Sutherland.

You know those brief moments in life when you read a book, watch a film or listen to a song and think, “fucking hell, I feel so seen right now.”? This was it for me — Loss aversion, anchoring bias, prospect theory, satisficing, hindsight bias, and sunk cost fallacy. I finally had the words to explain what I saw and felt in poker. I discovered these biases in other people and exploited them to win.

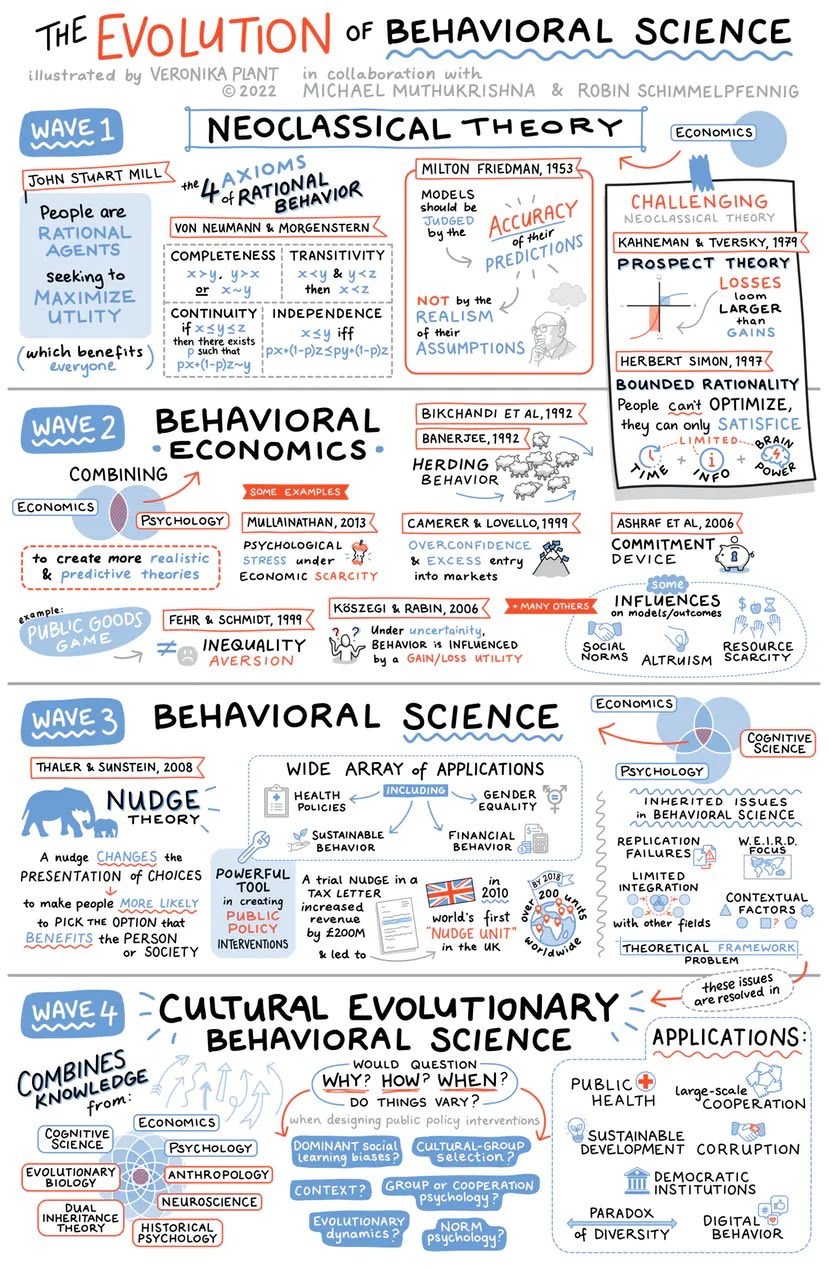

I read everything I could on behavioural economics (see list below), to eventually learning that the field had morphed into behavioural science — where the ideas are applied to other industries such as public policy and marketing.

Richard Thaler, who came up with the concept of ‘nudge’, talks about how it is used to get men to aim properly whilst peeing.

Behavioural science gave me the framework to, in part, answer one of life’s biggest questions: why do we behave the way we behave? — The short answer: It depends on context.

Behavioural science has also advanced my personal and professional life. I know how to easily create and break habits, learn new skills, and decide effectively. I also apply behavioural insights to business, marketing and advertising.

Here Are Some Of The Books I Read:

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini

Alchemy by Rory Sutherland

Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely

Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth & Happiness by Richard Thaler

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioural Economics by Richard Thaler

Inside The Nudge Unit: How Small Changes Can Make A Big Difference by David Halpern

Indistractable: How To Control Your Attention & Choose Your Life by Nir Eyal

The Upside of Irrationality by Dan Ariely

The Darwin Economy: Liberty Competiton, and the Common Good by Robert H. Frank

Evolutionary Ideas: Unlocking Ancient Innovation to Solve Tomorrow’s Challenges by Sam Tatam

Hidden Games: The Surprising Power of Game Theory To Explain Irrational Human Behaviour by Hoffman Moshe

The Elements of Choice: Why the Way We Decide Matters by Eric Johnson

Everybody Lies: What The Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz

The Illusion of Choice by Richard Shotton

An Interesting Moment In Time

Heart surgeons have figured out how hearts work. Aeronautical engineers know how planes fly. But by comparison, our understanding of the brain is still primitive. The truth is, even though we all have one, we don’t know how our brains work.

However, we’re at an interesting moment in time. As you can see in the infographic in wave 4, neuroscience is now a part of behavioural science. We now have neuroimaging technology to help us better understand ourselves.

I briefly studied neuroscience at university (2010), and the technology was still in its infancy. But since then, neuroimaging technology has innovated, and I remain optimistic that what we learn from neuroscience will grow exponentially.

For example, a few hundred years ago, we thought feelings of love originated in the heart. But now we know that our brains produce our emotions.

Understanding The Brain and Its Secrets

Traditional economic theory assumes that humans make rational decisions. According to economists, we do a cross-benefit analysis of every decision we make in life — We don’t.

I saw all the time at the poker table how irrational people are — myself included. The truth is we decide with our emotions and post-rationalise them.

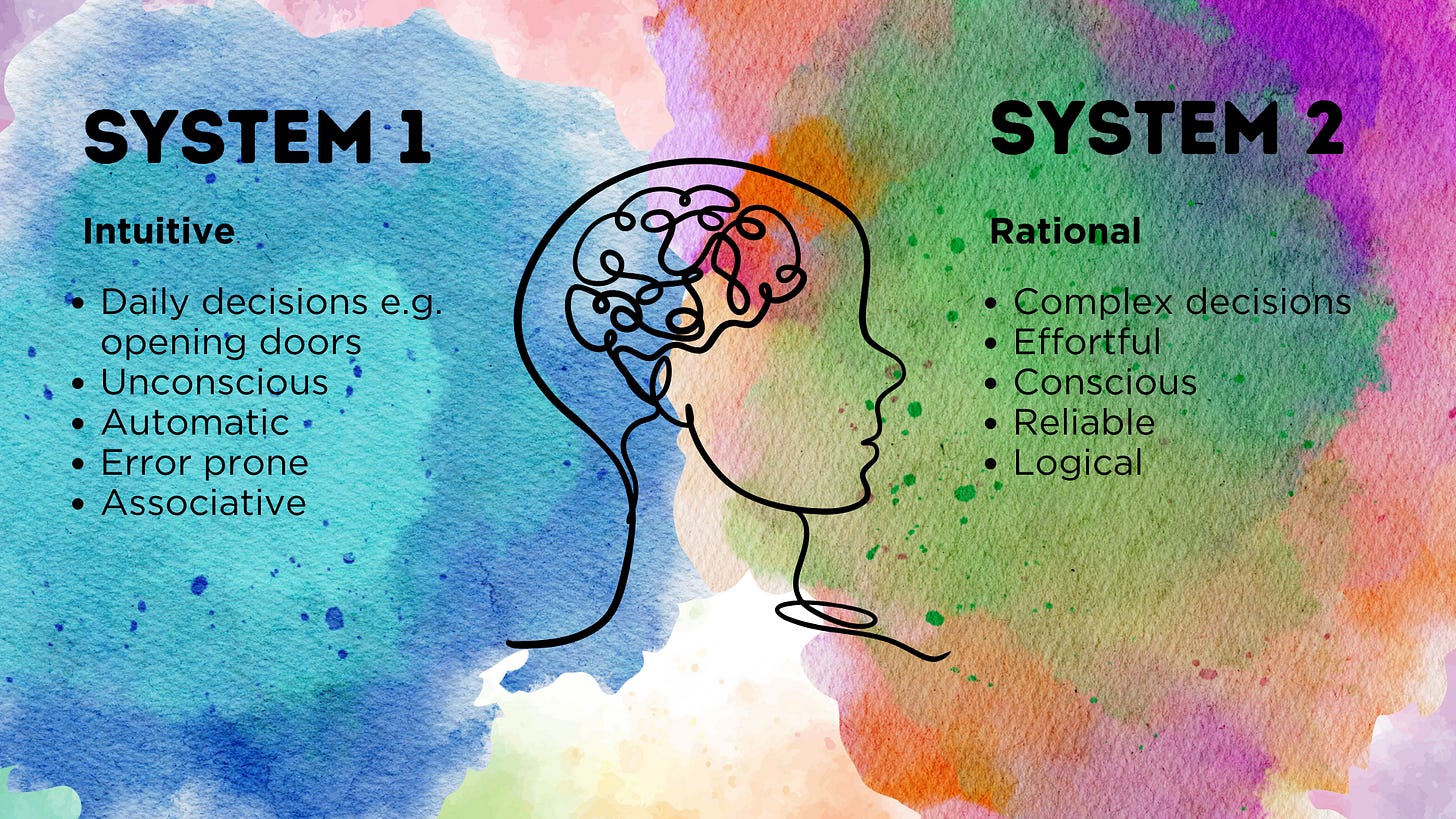

Over the years, there have been many theories on how our brains function: Left brain vs. right brain, logical vs. creative. But the one that has been the most widely recognised and easy to understand is Daniel Kahneman's System 1 and System 2 thinking.

Personally, I prefer Jonathan Haidt’s analogy of The Elephant and The Rider. It’s similar to Kahenman’s Systems 1 & 2 theory but more evocative.

Haidt argues that we have two sides: an emotional side (the Elephant) and an analytical, rational side (the Rider). The Elephant provides the power for the journey. However, the Elephant is irrational and driven by emotion and instinct. The Rider is rational. He or she can see the path ahead and do their best to guide the Elephant.

“The conscious brain thinks it's the Oval Office, but it is actually the press office.” – Jonathan Haidt

The Experiencing Self

The second time I ever did LSD, I became an existentialist.

While lying down on my friend’s sofa, I kept pondering these questions: If we’re all made up of the same atoms and elements, what makes us different? What gives us consciousness?

Philosophy has spent centuries trying to answer these questions about the human mind.

Unfortunately, I don’t know. I never managed to unlock the secrets of the universe on that acid trip. But I do know that somehow the big jumble of neurons gives us consciousness, and we seem to be aware of our experiences. As Daniel Kahneman said, “Odd as it may seem, I am my remembering self, and the experiencing self, who does my living, is like a stranger to me.” In other words, the way we feel in the moment of experiencing something is different from the way we feel when we recall it later.

Our brains are constantly changing it memories to better suit our needs, i.e. making themselves look better, exaggerating certain parts, and downplaying others parts without our conscious knowledge. An example of this is heartbreak.

How we feel depends on our interpretation of what is happening to us and around us — our attitudes. It is not so much what occurs but how we define events that determine how we feel. As Samantha, the AI bot, said in the movie Her, “The past is just a story we tell ourselves.” Once you realise your remembering self is just telling stories, you can change the narrative by reinterpreting it differently — This is the essence of therapy.

The Malleable Brain

“It’s too late for me to learn Italian.”

“I’m too old to start a new profession.”

“I’m too old to learn how to draw.”

If you find yourself saying something along these lines, I want you to know that these are all excuses. Here’s why it’s never too late to do anything new.

There’s a concept in neuroscience called Neuroplasticity. To put it simply, the brain has the ability to change.

There are tiny cells in your brain called neurons. The more neurons you have, the more connections you build between them and the better your brain functions. See it like a muscle — the brain works better the more you train it.

Changing who you are is possible. So go learn that new language, instrument or skill and become who you’ve always wanted to be.

“Your last day on Earth, the person you become meets the person you could have become.” — Dan Sullivan

Biases and Heuristics

We’ve now come to one of my favourite topics within behavioural science: biases and heuristics. These two underpin the art and science of decision-making.

So, what is a heuristic? Heuristics are mental shortcuts that help us problem-solve and make probabilistic judgements. It generalises or creates rules of thumb to reduce cognitive load. They can be effective for making immediate judgements. However, they often result in illogical and irrational judgement, a.k.a biases.

In poker, you have limited time (often 1 minute or less) to make a decision. As a result, you rely on heuristics to figure out what range of hands your opponent has, whether they’re bluffing or betting for value and what you want to do against them. The beauty of poker is that it gives you a fast feedback loop on your decision-making skills.

It’s not just the poker table that we use heuristics and biases; we use them in all sorts of real-world situations. For example, the availability heuristic is a mental shortcut that prioritises infrequent events based on recency and vividness. If a plane crashes and makes headline news, this causes people to be more fearful of flying. However, flying by plane is the safest mode of transport, and the likelihood of dying in a car crash (1 in 5,000) is far higher than in a plane crash (1 in 1.2 million). [Note: I used the availability heuristic of plane crashes because of 9/11].

The ease of recall depends on how recent and vivid something has impacted you. This means it’s easier to base your decisions on recent events compared to something that doesn’t easily come to mind. However, efficiency =/= effective. Recalling plane crashes and avoiding flights isn’t an effective decision, given the odds. As Kahneman writes in Thinking, Fast and Slow, “The brains of humans contain a mechanism that is designed to give priority to bad news.” It also explains why negative headlines are more salient and effective in grabbing our attention.

Why Is It Important To Understand Heuristics and Biases?

The etymology of ‘decide’ comes from the Latin word decidere — which means to cut off. Deciding one thing is choosing to cut off all possibilities. Therefore, knowing how to decide well is essential. I’d argue it is the most important skill because decisions are the unit economics of life.

And we often use heuristics to make those decisions. However, heuristics can cause us to form cognitive biases and commit certain fallacies. As a result, we make poor decisions.

By being aware of heuristics, we can recognise its shortcomings and become better decision-makers.

From Poker To Marketing & Advertising

Having a deep understanding of heuristics and biases made understanding marketing and advertising a lot easier.

Consumers rely on shortcuts all the time when making purchase decisions. One heuristic that is frequently deployed by advertisers is the scarcity heuristic. When we’re assessing the value of something, we perceive something to be more valuable the rarer or exclusive it is — Think luxury products.

Here’s an example of the scarcity heuristic being deployed by Patek Philippe. The ad obliquely implies a “limited quantity” and exclusiveness message, increasing a potential consumer’s intentions to purchase. This ad has been so effective they’ve been running it — with slight variations — for almost 26 years.

— Jason Vu Nguyen

P.S. Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed that and feel inclined, please share it with someone else you think will enjoy it too.